Poetry curated. Believing poetry can change the world, the intention here is to introduce and discuss compelling poems. My desire is to invoke a sense of longing in you to find a poem and a poet whose work speaks to your soul. When it happens, it can set your skin ablaze. In a good way.

Recently, my friend Jay came over for a Sunday afternoon poetry workshop. We hadn’t seen each other in quite a while- enough time had passed to learn he is working on a screen play and I’m recently married. As we settled into our workshop time, we kicked it off with writing prompts. Later we exchanged poems, providing feedback and the conversation expected during a workshop. I highly regard him as a friend who writes poems in form and meter with litheness of pen, and he shared some tips for me as I set out in my exploration of writing in rhyme and meter.

If you ever get the chance to ask a poet what they are reading and what is inspiring them, stand back. The answers are mellifluous! Jay shared the poem below with me and I in turn am sharing it with you. Poetry is like that- it’s meant to be shared.

The poem “Tucson” by Stephen Dunn is not the kind of poem that shimmers with adjectives. I think the spare description in this narrative poem builds such a fantastic tension that’s augmented in the line “but I’m not important.” – the narrator wants all eyes on the scene unfolding. Even the line length seems like a stilted dance with some short lines and others that are long in this tight poem. The poet builds the climax by naming the frailty of the human body instead of naming the fight breaking out. “I’d forgotten / how fragile the face is, how fists too / are just so many small bones.” The dexterity of this line really calls out the humanity that is the point in this poem because there are a lot of people in the poem. And they are “Mexicans, Indians, whites.” The deft way the woman in question moves on to dance with another woman after the fight breaks out points to fights being a regular occurrence. Even the narrator’s hands “were fidgety, damp.” This poem encapsulates place by naming it after a city and using the scenario of a bar fight to describe the tensions among its inhabitants.

It’s an interesting way to consider writing a poem. If you were to write a poem about your city, how would you structure it? Where would it take place and what would be the core essence of your city you would want as a grand take-away?

______________________________

Tucson

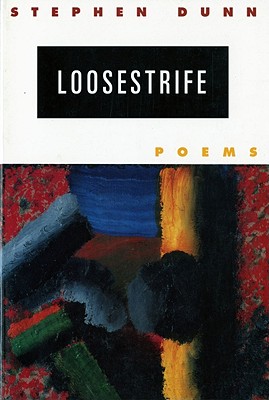

by Stephen Dunn from “Loosestrife“

A man was dancing with the wrong woman

in the wrong bar, the wrong part of town.

He must have chosen the woman, the place,

as keenly as you choose what to wear

when you dress to kill.

And the woman, who could have said no,

must have made her choice years ago,

to look like the kind of trouble

certain men choose as their own.

I was there for no good reason myself,

with a friend looking for a friend,

but I’m not important.

They were dancing close

when a man from the bar decided

the dancing was wrong. I’d forgotten

how fragile the face is, how fists too

are just so many small bones.

The bouncer waited, then broke in.

Someone wiped up the blood.

The woman began to dance

with another woman, each in tight jeans.

The air pulsed. My hands

were fidgety, damp.

We were Mexicans, Indians, whites.

The woman was part this, part that.

My friend said nothing’s wrong, stay put,

it’s a good fighting bar, you won’t get hurt

unless you need to get hurt.

This is great.

The fact that the poet knows what a “good fighting bar” is is cool. Now I’m craving shrimp and grits.

Right?

S. Dunn is a master and a masterful poet.

The zing of recognition of the frailty/impermanence/importance of life and living is aways there

at the end and always coming in a Stephen Dunn poem. And so it is with “Tucson.”

Starts out as a good story, perhaps as plot for a western or a tune accompanied by strums from the latest folksy singer.

Wrong woman, wrong bar, wrong part of town.

A bar rife with conflict and a whole lot of wrongness: man/woman, dancing/killing, Mexicans/Indians/whites, and the blood-raising difficulty of a woman “part this/part that.”

But wait. “Nothing’s wrong” because all those schisms are inside the “good fighting bar” container,

like the worm in the mezcal. It’s all good.

There’s protection, man: the bouncer will step in and someone will always grab a bar rag and wipe

up the blood. So drink up, “you won’t get hurt.”

Except it’s not a movie and there is no container.

You will get hurt if “you need to get hurt.”

Oh my.

The gonging playfulness of repeating the word “wrong” at the outset that sucked us in to this particular story just got shattered like a fifth of Wild Turkey smashed on the barroom floor.

It couldn’t stand up to the double use/double dose of “hurt.”

Fantastic comments Janet! I really loved the wordplay in this poem. I love your comparison that the scenery is like the worm in the mezcal. Yes! And I love how he turns this on its head. You think you know what to expect, except you don’t at all. The fragility is lingering underneath the surface of things that seem familiar or sturdy.